Effective online teaching strategies

In this blog post, Paul Flecknell provides some ideas for using the teaching and learning resources on this platform.

In a previous blog post, Jon Gledhill and I discussed the exciting launch of our new e-learning modules on RAT and elaborated on the benefits of incorporating e-learning into training courses. After engaging in conversations with course providers, I realised the value in providing a more comprehensive outline of how I use the resources on RAT in various training courses. This blog post will also provide a brief overview of the educational principles that inform my approach.

Around 20 or so years ago, I radically changed the anaesthesia training course at Newcastle University. Instead of a series of PowerPoint seminars on different anaesthesia topics, the course content was structured around a series of scenarios involving anaesthesia of different species. The participants were given a set of notes on the subject, and asked to read them before they attended the course. The new format created lots of discussion both on the main scenarios, but also more generally about how the participants would use anaesthetics in their research projects. What I didn’t know at the time was that I was “flipping the classroom”. This style of teaching has been gaining considerable attention, and is particularly relevant when using on-line resources such as RAT. So what is being “flipped” and how do we move to using the approach in our courses?

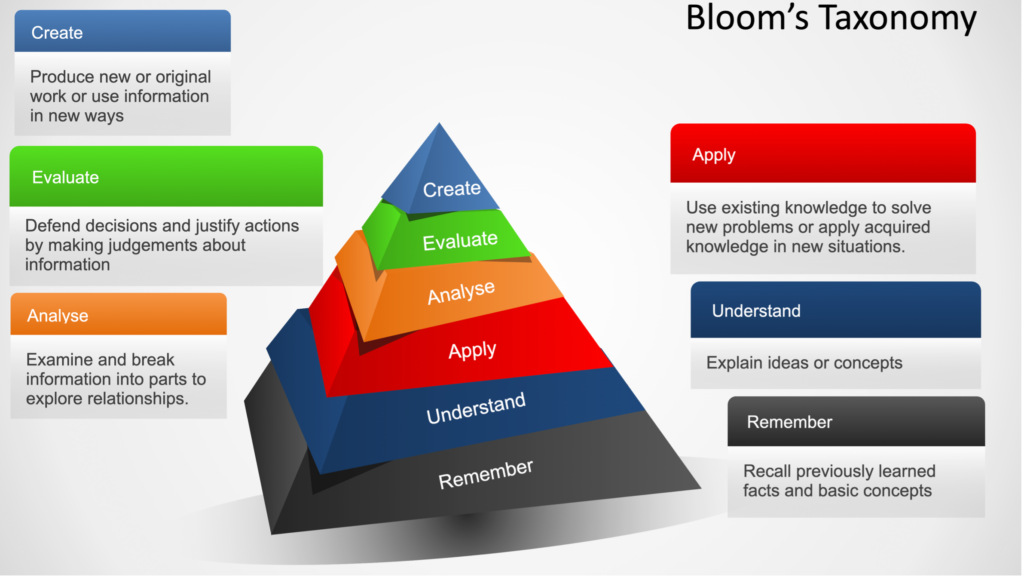

Many of us are probably familiar with the widely-known concept of “Bloom’s taxonomy”, specifically from our encounters with the discussion on learning outcomes and assessment in the EU Education and Training Framework. This framework, despite its origin dating back to 1956, underwent significant redevelopment and revision in 2001, as reflected in the version presented in the EU document. What isn’t shown is Bloom’s original schematic of a pyramid of tasks with the most complex and demanding at the top.

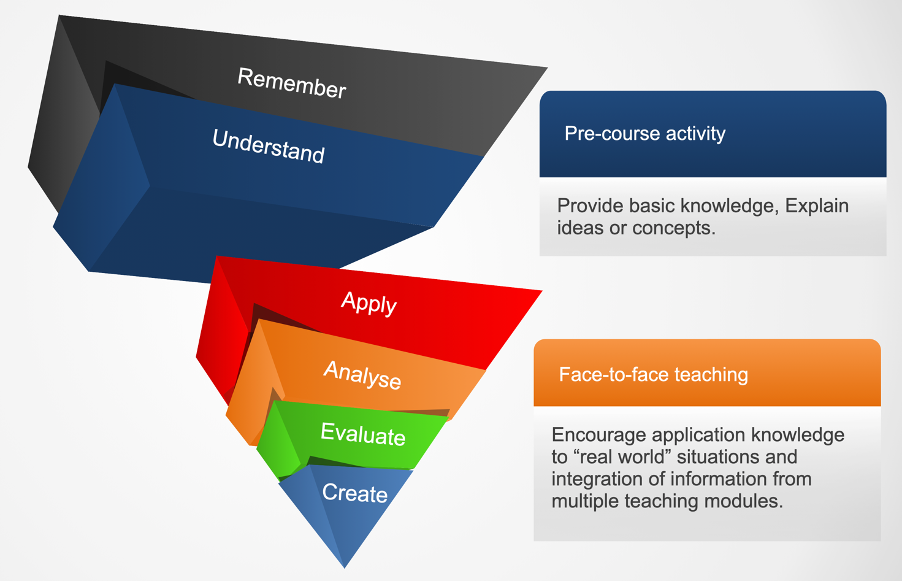

Think for a moment about how these tasks are handled in a typical training course. We provide the facts and basic concepts (“remembering“ and “understanding”) and perhaps explain some of them (“applying”). We then expect our course participants to be able to use this information in their research activities (“applying, analysing, evaluating and creating”). Since our students often attend our courses with almost no knowledge of the topics, it’s not surprising that we focus our teaching time on the bottom sections of the pyramid. Suppose instead, we move this part of the course into student self-instruction through structured activities, and focus our face-to-face teaching on the upper sections of the pyramid. This lets us give most support to these more complex tasks, and lets us encourage the application of the students’ learning activities to “real world” situations. In other words, we “flip” the pyramid and our approach to teaching our course.

So what self-instruction should we provide? This could be a recording of the lecture that you would normally have given, it could be a set of training notes, it could be one or more e-learning modules, or a combination of these activities. An advantage of using resources provided on RAT is that you can check the progress of your students and send out e-mails reminding them to complete the content before your face-to-face sessions. For the face-to-face sessions we need to develop more complex tasks to use the information from this self-instruction. Some online tools can help with this – we have used “Mentimeter” (www.mentimeter.com) for many years, both in face-to-face and on-line teaching. This, and similar tools, enable course instructors to build up scenarios, prompt interactions with questions and provide immediate feedback, as well as giving you a record of the discussions. In my own teaching I have also used “padlet” boards (www.padlet.com) for a more open-ended approach, particularly suited to recording small group activities.

As far as content goes, anaesthesia and analgesia is an easy topic – simply present a scenario: “A research group plans to anaesthetise 10 rats to carry out a craniotomy, they propose using pentobarbital as the anaesthetic, and state that analgesics cannot be used because they are contraindicated after intracranial surgery”. This gives lots of scope for recalling and applying the information given via RAT, but it can go much further – for example prompting a discussion on why 10 rats are being used, why rats are being used at all, whether the appropriate approvals have been obtained, how the rats are being housed and handled and what refinements are in place?

How would you apply this to a different part of the modular training? Once again a scenario can be used: “A research group want to assess the efficacy of a new anticancer drug using a tumour model in mice” could encompass law, ethics, 3Rs, health and safety, biology and husbandry, disease control (“let’s use SCID mice and a xenograft model”) and as the course tutor you can develop the discussion in a number of different directions. You could also start out the session with a short quiz on one or more of the modules, and then use the answers to encourage questions and discussion – using “mentimeter” or similar tools work well for this. Another alternative would be to present a series of images of animal rooms, labs, techniques etc. showing suboptimal approaches and invite comments and critiques from the participants.

The type of research, species used and topics can be tailored to suit the particular audience and your Institute’s specific research programs. You may also want to expand on specific topics or learning outcomes that are not covered in the self-instruction materials, but these more formal sessions can be integrated as 10 minute “sound-bites” rather than being lost in a series of 45-60 minute monologues. Of course, once you recognise common areas that need reinforcing in this way, you can record your 10 minute “TED talk” and provide it to the student’s in advance.

The face-to-face content of your course should also include the opportunity to introduce key members of the animal facility team, to run a question and answer session on local processes and practices and reinforce key messages surrounding animal use and the development of your institute’s “Culture of Care”. This final area requires application of the top two sections of the pyramid (evaluating and creating) and may not fit neatly into the approach outlined above. But your students will be better prepared to carry out these more complex tasks if you’ve supported their learning with a “flipped” approach: “Remembering and Understanding” as preparation, “Applying and Analysing” during your face-to-face sessions, and encouragement to continue to develop this post-course. Finally, remember that when using RAT, the preparatory materials will always be available to students to refresh their recall of factual material.